No Joke, Norwegians Love Their Lefse

Delve into Norwegian history and it doesn’t take long for the discussion to include the Vikings. It seems their imprint is on most everything in the Scandinavian culture and food is no exception.

One of such culinary delights is lefse, a legendary Norwegian pastry that has been coupled with its mystical fish delicacy lutefisk to become the brunt of more than a few Ole and Olga jokes.

What did Ole say when he saw his first pizza? “Who threw up on that lefse.” But while pizza has grown to international popularity from its Italian roots, lefse has remained a staple of Norway’s culture, a testament to the hardiness of its people in some of the harshest of climates. Perhaps that’s why its connection to the Vikings, viewed by many to be the hardiest of all.

Somehow you can just see a rugged Viking eating lefse, and it likely happened. But unlike its culinary cousin lutefisk that can test the most adventurous among us with its lye-preserved fish and its peculiar aroma and texture, the finely rolled lefse presents a thin canvas on which one can embark on a culinary adventure.

It, too, has roots that date deep into Norwegian history, but the Hardanger lefse of that era is unlike the type that most Norwegians incorporate into their holiday celebrations today.

Any Viking lefse pastry would have been flour-based, as it wasn’t until exposed to potatoes from Ireland that it altered the recipe and the more conventional lefse of today took form. At least here in America.

Well, the form hasn’t changed much over time, but what people do with these wraps certainly has. A delicacy that for so many needed simply a pad of butter or some sugar to serve as the rolled-up filling, now is open to one’s imagination.

Sigrid Slaby continues the tradition much like so many generations before her have: She learned from her grandmother.

Today, she shares her lefse with literally the country as her family’s business, Wienke’s Market, located near the Door-Kewaunee County line on County Highway S, is a magnet for lefse lovers.

“I grew up making lefse with my grandmother,” said Sigrid. “It’s a labor of love.”

In short, you have to love the labor, because there’s a lot of time involved in producing these legendary wraps – so much so that initially Sigrid’s team of lefse-makers at Wienke’s turns out a batch only once a week. With help from her father, potato peeling already begins on Sunday, and you can imagine the amount of peeling that goes into making 200-225 “rounds” in a day.

The first batch was assembled on Tuesday, Oct. 1, a date Sigrid said she regretted since it was a warm day.

“Everything got too moist,” she said.

What did Ole say when he saw his first pizza? “Who threw up on that lefse.” — Ole & Olga joke

Sigrid Slaby, center, and her busy crew began making lefse once a week in early October increasing to two-times-a-week in the weeks leading up to Christmas. Photo by Leslie Gast

That’s why lefse production is normally reserved for the colder months, starting early enough to insure enough product for Thanksgiving and Christmas. That requires that Wienke’s ramp up production to two days a week in November and December.

“When is this story coming out?” she asked, admitting that any additional publicity could throw her ingredient estimates out of whack. But production will continue to handle the Easter demand and ensure the store has enough supply to last into the summer.

“We normally run out around August,” said Sigrid, who laughs when she said the couple months without frozen stock only seems to drive demand once production ramps up again.

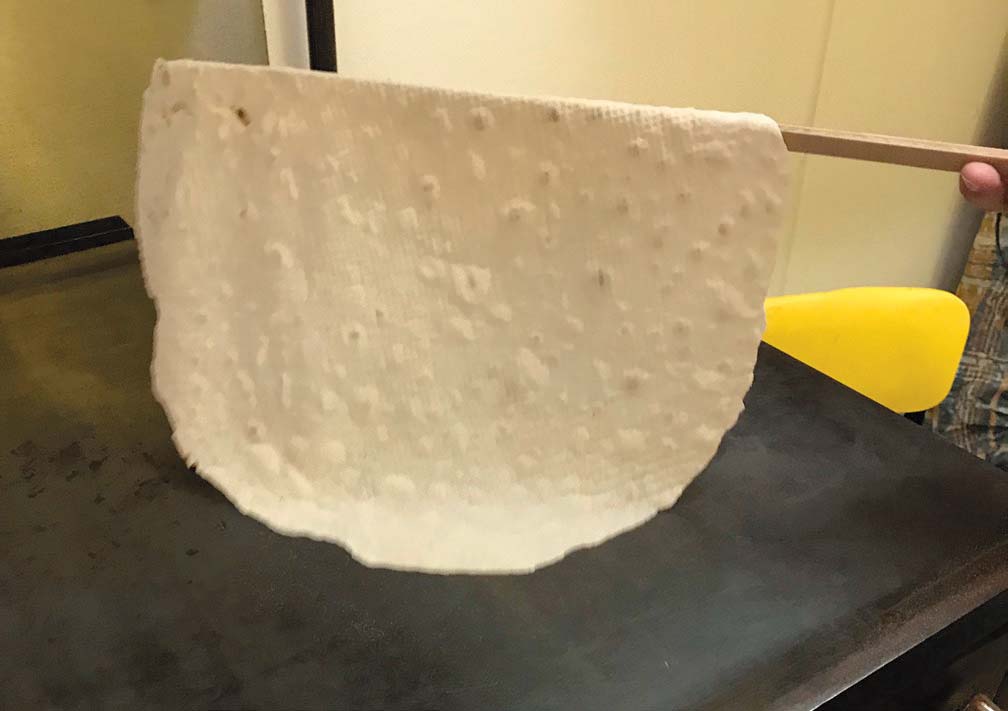

Inside Wienke’s kitchen you’ll find Sigrid pushing the potatoes through a commercial grinder; its spaghetti-like result is combined with salt and flour. It’s then formed into loaves and cut into biscuits before being rolled thin and baked on a fl at-top stove. Most unique to the process are the grooved rolling pins, handcrafted for Wienke’s to incorporate the flour into the dough.

“It is my grandmother’s recipe,” said Sigrid. But Edith Nelson did one thing that her granddaughter refuses to do. Sigrid doesn’t peel the potatoes after they are boiled.

“They are so blazing hot,” she said, ignoring her grandmother’s belief that boiling the spuds with their skins on produced more flavor in a delicacy that has been the brunt of jokes for being rather bland. Sigrid insists her lefse is fat-free, as it avoids the shortening and sugar in other lefse and holds to a basic recipe of potatoes, fl our and a little salt.

“It’s not what you put in it,” said Sigrid. “It’s what you put on it.” Often described as a Norwegian tortilla, lefse really is a wrap and can be enjoyed, as Slaby has always preferred it, with that pat of butter.

The delicate lefse coming off a flat-topped stove. Photo by Leslie Gast

“It is a potato wrap,” said Sigrid. “And as the popularity of wraps has increased, so, too, has lefse.”

And with that comes countless possibilities from sweet to savory. Dare say, some will even merge lefse with lutefisk, a traditional pairing for the most discriminating of tastes.

But just as Christmas cookies are a staple of the American holiday season, you won’t find many Norwegian-American homes without lefse being served and Sigrid with her band of merry lefse makers is doing its part to make sure this part of Norwegian culture is preserved.

“We ship all over the United States,” said Sigrid. “I can’t say for sure that we send to every state but just about every one.”

Sure, you can joke about lefse, but any food that has a lineage that has roots to a Viking dinner table and is so eagerly passed on from generation to generation deserves respect.

As Sigrid reminds us, it’s both a labor of love and a love of labor.